Encryption

With an understanding of what cryptography is and why it’s important, the question remains: how exactly does encryption hide messages? To examine this question — and some solutions — more closely, let’s write a program that allows two micro:bits to talk to one another: Micro:bit Messenger.

Hello, World

Let’s take another look at the script from the starter activity:

from microbit import *

import radio

radio.on()

while True:

if button_a.was_pressed():

radio.send("Mr Eric Praline") # Change this to your name!

new_message = radio.receive()

if new_message:

display.scroll(new_message)

Though primitive in nature, this could be considered a very simple free-for-all messaging program. Scripts of this kind simply consist of a series of commands that the computer should execute, from top to bottom. In this case, the code does the following:

- Import some handy conveniences to allow the script to easily manipulate various features of the micro:bit.

- Turn on the micro:bit’s radio to allow it to communicate over Bluetooth, a technology for wirelessly sending messages over short distances.

- Do the following forever:

- If the ‘A’ button was pressed, send a message over the radio with your name.

- Check for any messages from the radio, displaying anything that is found.

There is an obvious problem with this, though. Rather than have a single free-for-all shouting competition, we probably want to introduce some idea of distinct chats for different groups of people.

The radio in the micro:bit doesn’t allow you to send messages directly to one person — anyone can listen in on your conversation. Instead, groups of messages can be differentiated by a channel. Sending messages over multiple channels is similar to the transmission of multiple radio stations. Different stations broadcast on different frequencies at the same time, but your car radio — though it could listen to all the stations simultaneously — is set up to only listen to one channel at a time. After all, nobody wants to listen to One Direction, The Beatles, and Metallica all at the same time.

Within a particular channel, there are further ways to distinguish between messages such as sending with and filtering by a particular number called an ‘address’ (much like a postal address). We can configure the radio to listen and send only on a particular set of related communications — e.g. address 50 on channel 3 — by adding the follow command after enabling the radio:

radio.config(channel=7, address=50)

You can try this with your partner. Add the above line to the script we used previously — choosing a channel between 0 and 100 and an address between 0 and 4,294,967,295 — and watch how the conversation suddenly seems so quiet. Despite appearances, however, this conversation is far from private! Every message is still being broadcast for all to see, it’s just that most devices are keeping themselves to themselves and not eavesdropping. So how can we go about resolving this issue of privacy?

Cryptography!

Thankfully, our old friend cryptography is here to save the day. If we scramble our messages such that only the intended recipients are able to unscramble them, our secrets are safe. Anyone listening in may intercept the scrambled message, but they won’t know what to make of it. But how should we actually go about muddling up our messages in this way?

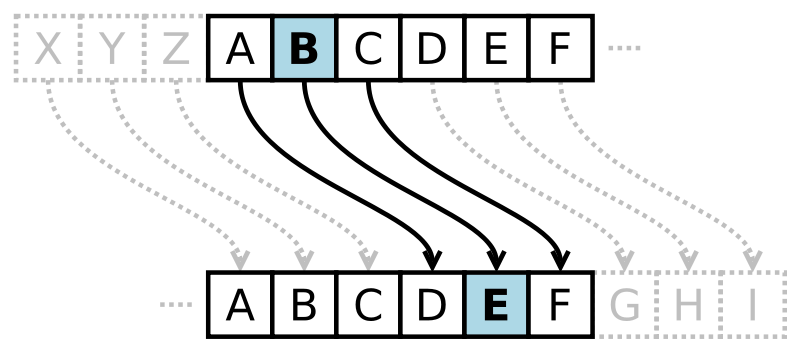

One simple solution, which has been used since at least 50 BC, is the shift or Caesar cipher. This replaces each letter in the plaintext (the raw message we want to transmit), with a different letter some fixed number of positions away in the alphabet, wrapping back around to the ends of the alphabet when necessary. If we choose to shift three spaces down the alphabet, for example, all As become Ds, Bs become Es, Xs become As, etc.

Each letter is replaced by another three letters down in the alphabet

Under this scheme, the plaintext “The quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog” is transformed into the ciphertext (the result of cipher encryption) as follows:

Plaintext: The quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog.

Ciphertext Wkh txlfn eurzq ira mxpsv ryhu wkh odcb grj.

This ciphertext is then broadcasted, and any valid receiver of the message — with whom this code of shifting three places to the right has already been established — then needs only to shift each letter back three places. A becomes X, D becomes A, E become B, etc. This seems like a clear improvement on transmitting plaintext, so let’s integrate this idea into our messaging program.

We’ll start off by shifting our message by a fixed number of letters. Look at the script below. You’ll need to:

- Decide on a channel with your partner, and both use the same channel

- Set your name

- Choose a number of letters to shift your message by (keep this secret!)

Then you can flash it to both your micro:bits, press the ‘A’ button and see what happens. You should see a scrambled message on the other micro:bit!

from microbit import *

import radio

def shift_letter(letter: str, amount: str) -> str:

if (letter == ' '):

return ' '

letter_num = ord(letter.upper()) - ord('A')

shifted_letter_num = (letter_num + amount) % 26

return chr(ord('A') + shifted_letter_num)

def shift_message(message: str, amount: str) -> str:

shifted_message = map(lambda l: shift_letter(l, shift_amount), message)

return ''.join(shifted_message)

radio.on()

radio.config(channel=7) # Choose your own channel number

shift_amount = 5 # Choose the number of letters to shift by

while True:

if button_a.was_pressed():

radio.send(shift_message("Mr Badger", shift_amount)) # Change this to your name!

new_message = radio.receive()

if new_message:

display.scroll(new_message)

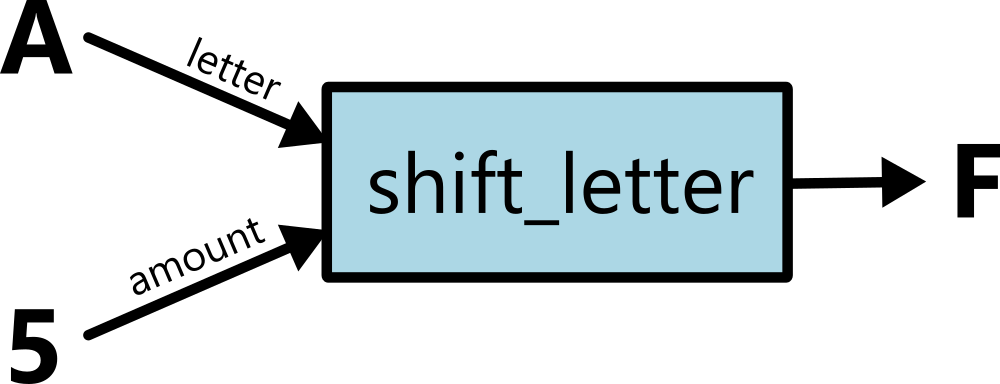

Whew! That script has quite a bit to unpack. You might have noticed the sections beginning with def shift_letter and def shift_message. These are ‘functions’: just like in maths, they take an input, do something to it and produce an output.

shift_letter

Let’s look at shift_letter first.

def shift_letter(letter: str, amount: str) -> str:

if (letter == ' '):

return ' '

letter_num = ord(letter.upper()) - ord('A')

shifted_letter_num = (letter_num + amount) % 26

return chr(ord('A') + shifted_letter_num)

The purpose of this function is simple: you give it a single letter (letter) and a number (amount), and it shifts the letter by that number. So, for example, if you asked for shift_letter('A', 1), you would get B. If you requested shift_letter('G', -3), you would get D.

The shift_letter function takes a letter and a number, and shifts the letter by that number

shift_letter

Let’s break down what shift_letter is actually doing.

if (letter == ' '):

return ' '

First (to keep things simple) we decide that we don’t want to do any shifting of spaces. So, if shift_letter is given a space character, it will just return another space.

letter_num = ord(letter.upper()) - ord('A')

ord

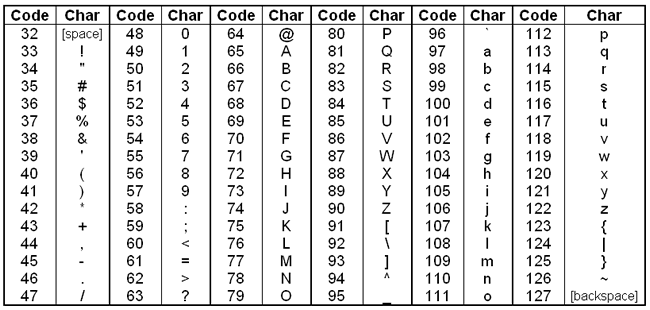

There are a few things to look at here. First of all, what does ord() do?

Well, simply put, it changes any letter into a number. Every letter has a unique number. Here’s a table of some of the common ones:

Image from http://macao.communications.museum/eng/exhibition/secondfloor/MoreInfo/Displays.html

You can see from this that when we call ord('A'), we must get 65 in response. If we call ord('V'), we’ll get 86.

Can you see a slight problem here?

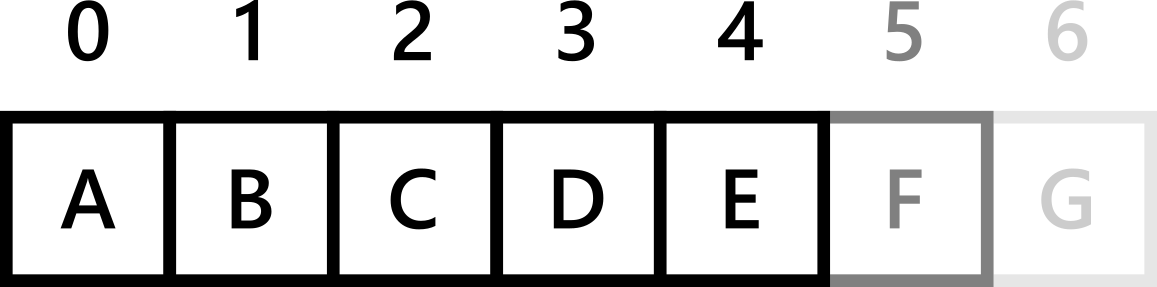

‘A’ is the first letter of the alphabet, and ‘V’ is the 22nd - not 65th and 86th! Actually, when we are storing a list in a computer, we normally refer to the first thing in the list as the zeroth (0th) thing, the second thing as the first and so on - like this:

Image from http://macao.communications.museum/eng/exhibition/secondfloor/MoreInfo/Displays.html

So, how can we turn ‘A’ into the number 0 and ‘V’ into the number 21? There’s an easy solution! Just subtract the number for ‘A’ from the number for the letter:

ord('A') - ord('A') -> 0 Because A is the 0th letter of the alphabet

ord('V') - ord('A') -> 21 Because (starting from 0) V is the 21st letter of the alphabet

Remember, functions like ord are documented in the official Python manual. If you’re ever stuck, try looking things up here!

.upper()

Calling .upper() on a string of text will produce an entirely-uppercase version of that string. For example:

"Hello there!".upper() == "HELLO THERE!"

We do this to the letter because shifting both lowercase and uppercase letters gets a lot more complicated! If we just stick to using uppercase letters for everything, we can reduce the amount of code we need to write.

shifted_letter_num

Having translated the input letter to a sensible number that represents its uppercase equivalent, we need to actually do the letter shifting. As letters that are next to one another in the alphabet are represented as numbers with this same property, we can shift a numeric representation up the alphabet by simple addition. In this case, we wish to move amount places down the alphabet, and so can get our result from letter_num + amount.

There is a problem with this approach, however. What happens to the letter ‘Z’? If we follow this logic with a shift of three, we will get 25 + 3 = 28 — as there are only 26 letters in the alphabet (numbered 0, 1, …, 25), this is not a desirable result! Instead, we want to wrap around the alphabet when necessary, so ‘Z’ should translate to ‘C’ (represented by 3) after a shift of amount 3.

To accomplish this, we simply want numbers greater than 25 to wrap back around to the start. This can be achieved using the modulo operation — represented by the percentage symbol % — which finds the remainder after dividing two numbers. So 15 % 26 will give a remainder of 15 (as 15 is zero 26s plus 15), 26 % 26 will give a remainder of 0 (as it divides perfectly), and 28 % 26 will give a remainder of 3 (as 3 is one 26 plus 3). This is exactly the behaviour we want, and so our shift calculation is: shifted_letter_num = (letter_num + amount) % 26.

return

With this number representing the letter resulting from the shift, it’s important not to forget that we’ve been working with all our numbers after subtracting ord('A'). To get back to the original numbering system we can simply add this back on, returning this value as the output of our function: return chr(ord('A') + shifted_letter_num).

Message Selection

We’ve done it, we’ve implemented a basic shift cipher! Sending a predetermined message like your name isn’t terribly useful though. Messaging apps usually let you choose a message for yourself. So let’s do that!

The micro:bit isn’t a device designed for long-form textual input, so writing messages won’t be the easiest, but it can be done. We can use the two face buttons to scroll through the alphabet — displaying the current letter on the LED grid — and can send the letter when both buttons are pressed in parallel, slowly building a message. This arrangement is a little clunky, particularly if you’re hoping to write a bestselling novel, but for our purposes it will suffice.

As the focus of this activity is to learn about encryption rather than input mechanisms, our final program to send and receive encrypted messages over a particular radio channel follows. If you’re curious to learn more about how get_letter works, the general idea is that we display the current_letter that has been selected until it is detected that both buttons have been pressed, at which point the letter that was selected at this time is given as the output of the function.

Sender program

This program is only capable of sending messages, not receiving them. Flash it onto one of your micro:bits and try sending a message. What appears on the other micro:bit? Can you decode it?

from microbit import *

import radio

radio.on()

radio.config(channel=7) # Make sure you are using the same channel number as the receiver!

def get_letter() -> str:

current_letter = 'A'

choosing = True

while choosing:

sleep(300)

display.show(current_letter)

button_a_pressed = button_a.was_pressed()

button_b_pressed = button_b.was_pressed()

if button_a_pressed and button_b_pressed:

choosing = False

elif button_a_pressed:

current_letter = shift_letter(current_letter, -1)

elif button_b_pressed:

current_letter = shift_letter(current_letter, 1)

return current_letter

def shift_letter(letter: str, amount: str) -> str:

letter_num = ord(letter) - ord('A')

shifted_letter_num = (letter_num + amount) % 26

return chr(ord('A') + shifted_letter_num)

display.scroll("Choose shift")

shift_amount = 0

choosing_shift = True

while choosing_shift:

sleep(300)

display.show(str(shift_amount))

button_a_pressed = button_a.was_pressed()

button_b_pressed = button_b.was_pressed()

if button_a_pressed and button_b_pressed:

choosing_shift = False

elif button_a_pressed:

shift_amount -= 1

elif button_b_pressed:

shift_amount += 1

while True:

chosen_letter = get_letter()

display.show(chosen_letter)

radio.send(shift_letter(chosen_letter, shift_amount))

sleep(2000)

Try it out. It’s primitive, but it works! You can send messages between two micro:bits without eavesdroppers reading what you wrote… or can you?

Breaking Codes

For as long as there has been cryptography and codes, there have been people interested in breaking those codes. In your case, those people are the opposing team that you have been paired with!

Within your groups, two of you should try sending some messages to each other using the script above. Meanwhile, the other pair can listen on the same channel, using the script below. Remember that knowing the channel to listen on isn’t cheating, as listening on a different channel would simply mean that the micro:bit was actively filtering out your conversation data!

Receiver script

This new receiver script has a special feature. Read the code and see if you can figure out what it is.

from microbit import *

import radio

def shift_letter(letter: str, amount: str) -> str:

letter_num = ord(letter) - ord('A')

shifted_letter_num = (letter_num + amount) % 26

return chr(ord('A') + shifted_letter_num)

def shift_message(message: str, amount: str) -> str:

shifted_message = map(lambda l: shift_letter(l, shift_amount), message)

return ''.join(shifted_message)

def shift_message_simple(message: str, amount: str) -> str:

shifted_message = ""

for l in message:

shifted_message += shift_letter(l, amount)

return shifted_message

radio.on()

radio.config(channel=7) # Make sure you are using the same channel number as the sender!

# Remember, knowing the channel number isn't cheating.

message = ""

shift_amount = 0

while True:

button_a_pressed = button_a.was_pressed()

button_b_pressed = button_b.was_pressed()

if button_a_pressed:

shift_amount -= 1

if button_b_pressed:

shift_amount += 1

letter = radio.receive()

if letter:

display.show(letter)

message += letter

sleep(500)

letter = None

display.scroll(shift_message(message, shift_amount))

Once both teams have done this, each should have a piece of paper full of gobbledygook. The intercepted message is gibberish, the shift cipher is doing its job. There are a few things you might notice about the message, however. Notably, spaces and punctuation remain in tact, as they were not modified by the encryption. The spaces give us information about the length of words in the message — which are in the same order as they were sent — and the punctuation provides clues for what’s going on in the sentence.

Take the shifted sentence “L’p vhqglqj d phvvdjh” for example. It doesn’t take a rocket scientist to figure out that the single ‘d’ might be an ‘a’, or that the apostrophe in “L’p” might be a giveaway for “I’m”. And if we know for sure what one of the coded letters corresponds to, we can unshift the whole thing with ease. If ‘d’ corresponds to ‘a’ then that’s a shift of 3, so the sentence would be “I’m sending a message”. It checks out.

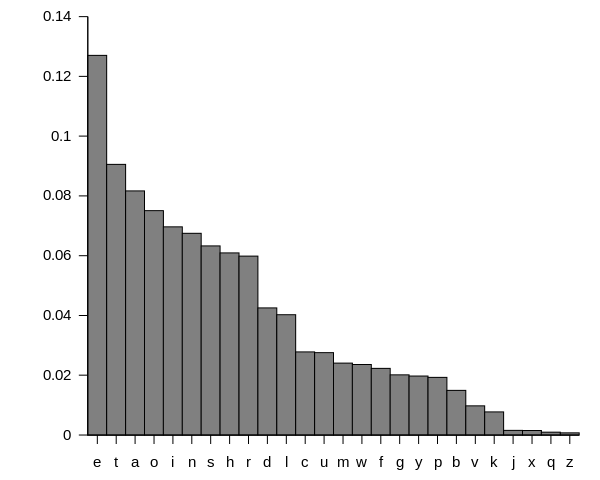

The problem here is that our encrypted language is too similar to English. All we’ve done is shift a few letters around by a fixed amount, and that makes our scrambled messages alarmingly close to regular ol’ English. One general purpose method for cracking codes by using this fact is called frequency analysis. This makes use of the fact that certain letters appear in the English language more than others. The letters in the previous sentence are ’e’s about 15% of the time, for example, which contrasts to the 3% rate you might expect if letters were chosen randomly.

In fact, ‘e’ is generally the most common letter in the English language, followed by ‘t’ and then ‘a’. By checking how frequently certain letters occur in the encrypted message — assuming that the writer more or less naturally follows the usual letter frequency distribution — you can determine which coded letters are likely to correspond to which plaintext letters.

The relative frequencies of letters in text, calculated by analysing a large number of written works.

Using this technique, try to decode your intercepted message. Look for patterns in the ciphertext that might correspond to quirks of the original message, and use the chances of different letters occurring to give you hints. Humans are naturally good at finding patterns, so with any luck you’ll have cracked the code in no time.

In the event that a reasoned, logical approach doesn’t yield a satisfactory result, it is always an option to try all the possible shift amounts! As there are only 26 different ways that our shift cipher can associate coded letters with plaintext letters, it’s not particularly time consuming to try each and see what it looks like. This is especially true if you get a computer to do the heavy lifting for you:

// TODO: Insert

It is clear, then, that the shift cipher isn’t an exceptionally strong form of encryption. It’s relatively trivial to break — especially for computers — and what’s more, it often isn’t even practical on the Internet.

Remember when you and your partner had to agree on a shift amount to use? If you weren’t physically next to one another to exchange this information, you would have to send a message containing it. But wait, if the whole problem we’re trying to solve is to send messages in secret, we would have to send this key piece of initial information — the piece that has the power to unscramble all of our encrypted messages — in regular unencrypted plaintext! That’s no good!

It turns out that this problem of communicating privately and securely is a bit of a tricky one. Over a shared medium like radio or the Internet, this often involves exchanging an initial piece of secret data that, like the shift amount in our cipher, has the power to decrypt the messages. This is done through a ‘key exchange’ algorithm, which performs the curious job of securely exchanging a secret piece of information over an insecure communication channel.

An encryption algorithm — like our shift cipher — then uses a secret to encrypt data. Unlike our shift cipher, however, it is desirable to have this be very difficult to break! This is a common theme in cryptography, that a chain is only as strong as its weakest link. There are always a number of different components in a ‘secure’ system that can go wrong, and — unfortunately — often times they do.

Despite these difficulties, it is important not to forget the critical role that encryption plays in our day-to-day lives. It is vital to protecting any information exchanged or held by computers. Your financial data, passwords, mobile phone conversations and emails. Your web browsing habits, current location, personal notes, private pictures. We are in dire need a society that better understands encryption. Having built a cryptographic messaging system, you have gained some of this insight.

Interested in finding out more about encryption? Why not have a look and see if your school library has a copy of The Cracking Code Book?